"Did you notice that every conversation of ours that's even slightly serious contains the word – world", Miki says at the Belgrade Railway Station platform. "In the world, from the world, world-wide... If one must live, then one should live the best possible way".

"World-class!", Bane added.

"Yes. As soon as I get my hand on a sum of money that can make a difference, I will go out to the world and acquire cash and a standard of living."

Bane disagrees. "You see, I believe it's a much bigger deal to create your own world here – where I was born – then going off to some foreign one. That way, some day, when the both of us are in a retirement home, some other two bozos, somewhere in Paris, at Gare de Lyon, will say: ’Going to Belgrade, now that's the real deal!’"

Bane and Miki are protagonists of the TV series "Unpicked Strawberries"[1]. Some people today would call it the most nostalgic Yugoslav TV show; it began airing in 1975 and it depicts the 1960s. A decade which had much promise and which spawned many Events. Somewhat paradoxically, one of the biggest events – the 1968 student protest – went without being mentioned in the program. Its co-writer and director Srđan Karanović told in an interview for "Vreme" weekly that seven minutes worth of material was removed from the ninth episode, seven minutes in which the main protagonist goes to the student protest, and even joins in the famous Kozaračko Kolo[2] after Tito's "the students are right"[3] statement. "It was a time in which nobody banned anything, but instead they would say that ’some fools will mind, so it's better for you to remove it’", Karanović explained.

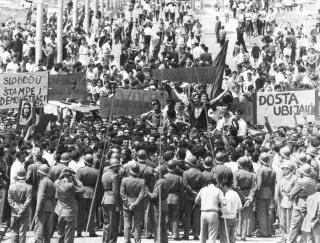

And indeed, 1968 brought in a degree of discomfort. It was difficult to face something as ambivalent. A protest against the government, on the one hand, but also a protest that supported the ruling policies as mapped out by their program. "We have no particular program", read the statement from the blocked Faculty of Philosophy signed by students and professors. "Our program is the program of the most progressive forces of our society – the Program of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia and the Constitution. We demand that they are consistently implemented." So the first rebellion that shook Yugoslavia after World War II was one that did not question the ostensible premises of socialism, but in fact the deviations from the road that had been promised. The protest also caused a major debate, both in the general public as well as within the party. To make matters more interesting, a large part of the active participants included members of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia. All together, it did render the protest an uneasy affair, but also a subversive one. However, today's context dominated by the anti-totalitarian paradigm still suppresses the possibility of perceiving the Yugoslav June Turmoil[4] without being burdened by the anti-socialist hysteria.

Third Pole

At the seventh European Historical Forum held in Berlin in mid-March this year, there was talk of 1968. Organized by the Heinrich Boell Foundation and the Memorial Research and Information Centre from Moscow, this forum gathered a large number of researchers interested in discussing everything that 1968 has spawned, even half a century later.

As for the topics, there is an abundance of them. They range from the student protests in Paris and Frankfurt, antiwar demonstrations, mobilization of students in Yugoslavia, to the Prague Spring and the March events in Poland. At times, it seems as though 1968 was as tumultuous as things ever got. Europe's image in that year has at least three dimensions. On the one hand, the struggle against the Soviet Union's repression, and the rebellion of Western European students against the repression exerted by capitalism, on the other. And, between these two poles – Yugoslavia.

At this year's Forum, such a triad-based approach could have been more pronounced, as it does not allow for a simplified dyadic representation of East and West that we have grown accustomed to in the past couple of decades. This was compensated by means of a separate workshop specifically dedicated to Yugoslavia. However, the vast majority of participants in this workshop were people from Yugoslavia.

Yugoslav Contradictions

What is so specific with regard to socialist Yugoslavia that it necessitates a more thorough processing? Above all, it compressed and coalesced the other two poles whose aspects refracted within Yugoslavia in a quite peculiar manner. Namely, both the authorities and the people supported the French students and the people of Vietnam. The Prague Spring was also widely supported. As part of the media coverage, one could read about both Daniel Cohn-Bendit and Alexander Dubček.

And one more thing. Since 1948, Yugoslavia embarked on its own path towards socialism, independently of the Soviet Union that dominated the Eastern Bloc. This path implied the abandonment of rigid planning and introduction of self-management, establishment of institutions – workers' councils and local community centers – aimed to enable the democratization of the economic and social sphere. The continuation of reforms led to decentralization and a gradual introduction of the market. Yugoslavia thus developed into a hybrid system which was frequently (and contradictory) dubbed – market socialism.

All rebellions that took place worldwide in 1968 were interpreted by the Yugoslav leadership as an indicator of the validity of the Yugoslav path toward socialism.

Still, new generations were coming of age, those that did not remember all that we lacked prior to World War II, but knew what had been promised by socialism. Unlike Germany where the generational clash in 1968 also implied facing the parents' national-socialist past, the conflict in Yugoslavia took on a different direction. Students wondered why their parents stopped building a more egalitarian and democratic society, why they settled for partial success. "The revolution is not complete!", as was bluntly stated by the students.

Dragomir Olujić Oluja, who took part in the student rebellion, received a telegram from his father immediately after the Faculty of Philosophy was occupied. "Don't get involved with that, there are people who should and who are in charge of solving those problems!", the letter read. Oluja then asked his father, who joined the ranks of the partisans as early as in 1941, about how he responded to similar warnings back in the day. Clearly the framework of what had been achieved was too narrow for the new generations' awakened expectations.

The economic reforms that were being gradually introduced constituted the main problem. As early as in 1950, management of the economy was transferred into the separate republics' jurisdiction, and as of 1958 individual enterprises that were allowed to manage their income have gained in importance. This manner of decentralization helped spread the influence of market mechanisms, and the competition among enterprises, as well as individual republics. After the 1965 economic reform, these tendencies only kept growing, resulting in mass sackings and deeper societal divisions. Whereas the nomenklatura saw the fact that enterprises were in the hands of workers' councils and that ownership was neither private nor state – in fact, societal – as sufficient proof of self-management socialism's validity, the students would not be fooled.

"Down with the red bourgeoisie!"

"Self-management from bottom to top!"

"Jobs for everyone!"

These were some of the slogans that accompanied the 1968 protests in Yugoslavia.

Overcoming the Discomfort

As for the party, it faced a problem contained in the fact that the rebellion was escalating beyond its ranks. Engaging in polemics is allright, but in a controlled environment. As soon as it is carried out in the street, things take a serious turn. After all, how is it possible that citizens of a successful socialist country rebel by demanding more socialism? A paradox. Similarly, workers' strikes gained momentum in the upcoming period. If we have self-management socialism, why are the workers protesting?

Here we can revisit Miki and Bane from the beginning of the text. The crisis that rattled the society was so deep that the student youth found itself facing two paths. With decreasing job prospects, one could either go "out to the world to get cash" or stay and try to keep struggling for something better. Millions of Yugoslavs took the first route, mainly becoming Gastarbeiters[5] who worked hard doing low-wage jobs in order to send money back to their families.

Those who stayed kept on struggling.

Therein lays another discomfort of 1968. After that year, mass rebellions are increasingly featured by national traits. We cannot say that 1968 was a turning point – the reforms that introduced competitiveness among republics and led to dissolution of solidarity have begun to set the scene for a nationalist upheaval much earlier. What can be said with certainty is that 1968 probably remained the last example of a mass revival of a utopian horizon in Yugoslavia. Was 1968 a success in terms of fulfillment of the immediate demands? Probably not. But it remains a success insofar as it symbolizes a struggle different than everything we have experienced during the last three or four decades. A symbol of a struggle for a different world that is possible.

[1] Originally entitled "Grlom u jagode", the TV series was a massive success throughout former Yugoslavia. It consisted of 10 episodes, each one depicting one year in the 1960-1969 period, a coming of age story seen through the lens of its main protagonist Bane – translator's note.

[2] A type of traditional circle dance, particularly popularized by Yugoslav partisans during the People's Liberation Struggle in WWII – translator's note.

[3] In a televised statement on June 9 1968, Josip Broz Tito acknowledged mistakes by the communist leadership, underlining that the current situation is not a reflection of an international movement but rather has to do with "piled up mistakes which need to be resolved". Tito's speech effectively marked the end of the protest, with many students joining in a circle dance and cheering Tito's name – translator's note.

[4] "June Turmoil" (original title: "Lipanjska gibanja") is also a 1969 short documentary film by Želimir Žilnik which depicts the student protest of 1968 – translator's note.

[5] German term, "guest worker", mainly referring to a formal employment program in West Germany after WWII; a bilateral recruitment agreement with Yugoslavia was signed in 1968, attracting many workers to move and work in West Germany – translator's note.